Big Bend Ranch State Park

Big Bend Ranch State Park is a huge state park just west of Big Bend National Park.

Big Bend Ranch State Park is a huge state park just west of Big Bend National Park.

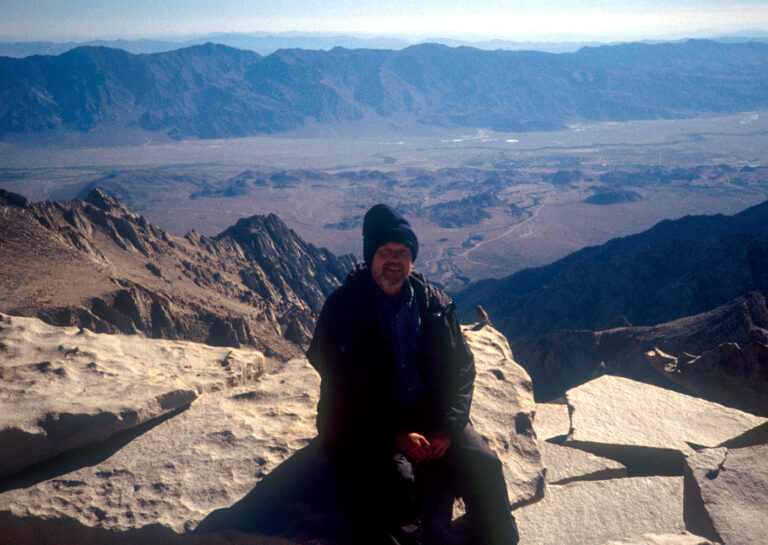

I completed a North to South thru-hike of the John Muir Trail in 2002. Here is a trip report of my hike. John Muir Trail day 1 – 3 John Muir Trail day 4 John Muir Trail day 5 John Muir Trail day 6 John Muir Trail day 7

Humphrey Peak Wikipedia In August 2003, on the way to California to my brother’s wedding, I camped near Flagstaff, Arizona and climbed Humphreys Peak, the high point of the state. The hike starts off in the “Snow Bowl”, a ski area, then winds its way up through the forest until it gets to timberline. Then…

I’ve hiked many times in the Indian Peaks Wilderness, just south of Rocky Mountains National Park. This time was a multi-day backpacking trip. Because of the nature of the trail system and the need for permits in advance, I planned a route with a sort of curly-cue path.

I left austin a bit late Friday (November 7), right at 9. This put my ETA at big bend at 17:30 and that’s exactly when i got into Panther Junction. Got a bag of ice in Marathon. Turns out they’d had 4 inches of rain the day before. Several roads were closed, so there were…

A November camping trip to Big Bend National Park.

It’s taken me a few years to figure this out. I’ve had a cheap old tarp in the past which I’ve almost never used; then, before my John Muir Trail hike I picked up a ultra-light Sil-Tarp (below) which was marginally effective but I still never really got the hang of pinning it down in…

ZPacks accessories sell some pretty nifty lightweight gear for hiking and backpacking.

Reflecting on a trip twenty years ago, the author shares insights on what they would alter, such as hiking later into the day to utilize camping spots better, and creating a detailed pre-trip spreadsheet for trails and sites. They also describe an effective, though simplistic, food routine involving freeze-dried meals and powdered milk that fulfilled their needs well. However, the author notes excessive packing of heavy clothing and inefficiencies in water storage, suggesting modern packs with built-in hydration systems as an upgrade.

September 9, 2002 31º-51º @UTY <- previous day | epilogue -> I was up early; and except for the water bottle in my bag still had to deal with some freezing. And since I had pretty much used up all the food, breakfast was a bit skimpy. But I anticipated the pizza slices at the store at…